Guide to Leveraged Finance (Lev Fin)

Leveraged finance, as we know it today, originated in the 1980s as the private equity industry developed and grew. Since then, the range of products and investors has grown and changed, with the most radical development – the rise of “debt funds” or direct lenders- occurring as a result of the Global financial crisis. leveraged finance is a critical tool for companies seeking to finance major transactions, such as acquisitions, leveraged buyouts (LBOs), and leveraged recapitalisations. This article will explain some of the intricacies of leveraged finance, exploring its definition, instruments, risks, rewards, and real-world applications.

Article Contents

- What is Leveraged Finance?

- Who Finances a Leveraged Finance Transaction

- Doing an LBO in the 2000’s

- How did the types of Financial Instruments for Leverage change

- Second Lien debt and Mezzanine

- High Yield Bonds

- Mezzanine Finance

- The Credit Crunch and the rise of the debt funds and unitranche

- Debt Restructuring and Distressed Situations

- Exit Strategies and Refinancing

- Risks and Rewards of Leveraged Finance

- Credit Rating Agencies and Risk Assessment

- US vs. European Leveraged Finance Markets

- Examples and Case Studies for Leveraged Finance

Key Takeaways

| Topic | Key Takeaways |

| Leveraged Finance Definition |

|

| Key Instruments |

|

| Market Evolution |

|

| Risks |

|

| Exit Strategies |

|

| Key Players |

|

| Regulatory Oversight |

|

What is Leveraged Finance?

Leveraged finance, often referred to as “Lev Fin,” involves using high debt levels. The average debt/EBITDA of non-financial companies in the FTSE100 is only 1.5X. In a leveraged transaction, like a Leveraged Buyout, we might see total Debt/EBITDA of 6.5X, immediately putting a new deal on the “naughty list” at the US Comptroller’s office!

If we talk in credit rating terms, Lev Fin lenders operate in the BBB and below investment grade areas. Banks typically bring leveraged and acquisition finance under one umbrella, so not everything acquisition they do is highly leveraged. Common definitions use debt/Equity >50% as a benchmark, or Debt/EBITDA>3 or 4X. Tax authorities use tests such as “is interest more than 50% of EBITDA” to decide if a deal is “leveraged” and to then restrict tax-deductibility of interest on the “excess” debt.

Who finances a Leveraged Finance Transaction

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis or credit crunch, leveraged finance and P/E led leveraged buyout financing was straightforward: For BBB and crossover credits (i.e. companies with one investment grade and one below investment grade rating) companies making acquisitions, banks provided senior debt, usually on an unsecured basis.

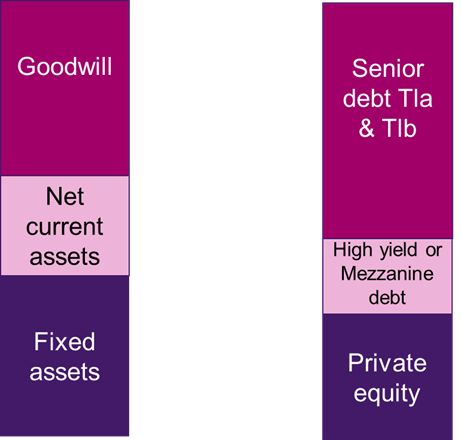

In leveraged buyouts where maximising leverage was usually a target, banks would provide senior secured debt; Mezzanine funds or high yield bond investors provided subordinated debt, or senior unsecured debt (so still effectively ranking after the banks). Private equity funds provided the equity.

Doing an LBO in the 2000’s

Three distinct developments happened between 2000 and 2006:

- Hedge funds began investing in leveraged loans and high yield bonds, attracted by the high spreads and betting that spreads would reduce (which they did).

- CLOs also exploded in number.

- Pension investing increased dramatically in Europe, creating an increase in demand for high yield bonds.

Leveraged Loans TLAs and TLBs

This senior secured debt was traditionally provided by banks in two tranches: an “A” tranche that amortised over 5-6 years and a B tranche a “Term loan B or TLB” which had a maturity of 1 year longer and a bullet repayment. Interest rates for leveraged loans can vary depending on market conditions and the borrower’s creditworthiness, but they typically range from LIBOR + 300 to 800 basis points.

Banks, because of their short-term funding base preferred the A loan and generally the B would be syndicated pro rata with the A loan. So, banks were forced to participate.

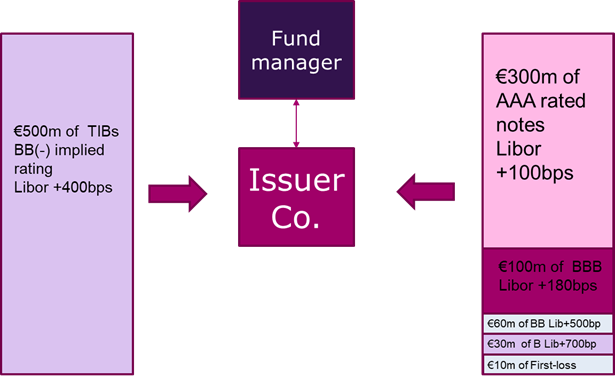

A CLO – a collateralised loan obligation is a fund which invests in floating-rate leveraged loans. It then finances itself by issuing a series of floating rate notes, each tranche of which is subordinated to the ones above it. Here is a typical structure.

The growth of the number of CLOs was a revolution in the European markets. Unlike banks the funds preferred the longer duration TLBs. The bond investors wanted long term assets of clearly defined duration. The opposite of the banks! This suited borrowers: “A loans” put progressively more pressure on cashflow as the amortisations increased over the life of the deal. B loans could just be refinanced in full on exit from the deal. Borrowers started to get all B loan deals and banks largely left the senior financing, being left with only revolving credit for working capital finance.

Second Lien debt and Mezzanine

The second impact of the CLOs was on the Mezzanine funds. Mezzanine debt was expensive typically with a coupon of SOFR +5.5% cash and 5.5% PIK or pay-in-kind. PIK means that the interest is added to the principal amount, so your debt balance goes up each year (and you interest bill!) In a small or medium-sized deal (i.e. too small to do a high yield bond), then Mezzanine was the only game in town if you wanted to extend leverage.

Leveraged finance CLOs are typically covenanted to have more than 85 or 90% of their investments in senior secured debt. Some innovative corporate financiers had the clever idea of marketing second lien debt as an alternative to Mezzanine. A “second lien” is a generic term for a second ranking claim over an asset. A mortgage is an example of a lien. In practice in the debt markets second lien lenders will share exactly the same collateral as the first lien lenders (here the A & B loans) but on a second ranking basis: they only get the proceeds of the asset sales after the A & B lenders have been paid in full.

This “innovation” suddenly meant that CLO funds became a cheap, alternative to Mezzanine in the form of Second lien debt. The second lien debt would go into the 80-90% pot of the CLOs with an enhanced yield.

High Yield Bonds

Another popular instrument in the leveraged finance realm is high-yield bonds. These bonds carry credit ratings below investment grade, reflecting the higher risk of default. However, they offer higher yields to investors willing to take on additional risk. High-yield bonds are frequently used to finance leveraged buyouts, mergers, and acquisitions, as well as to refinance existing debt. Yields on high-yield bonds can range from 5% to 12% or higher, depending on the issuer’s credit quality and market conditions.

High yield bonds can have different structures: they can be issued as senior debt, this would typically be the case for a “fallen Angel,” i.e. a company that has fallen on hard times and has fallen below investment grade, or for companies like Fresenius that just like being leveraged.

In large leveraged transactions, High yield bonds may be issued on a senior unsecured basis, but and it is a big BUT, with large amounts of senior secured debt ranking ahead of the high yield bonds the bonds are effectively very subordinated.

The growth of the high yield bond market in Europe and the growth of CLOs created great competition to Mezzanine funds. Using high yield and second lien could lower the cost of subordinated debt by several percentage points. These developments largely killed off Mezzanine as a product in medium and large LBOs.

Mezzanine Finance

Mezzanine finance is subordinated debt which ranks below senior debt but above common equity in terms of repayment priority. Mezzanine financing is often used as a complement to leveraged loans or alternative to high-yield bonds, providing additional capital for leveraged transactions. Mezzanine debt typically carries interest rates in the range of 12% to 20%, reflecting its higher risk profile.

The Credit Crunch and the Rise of the Debt Dunds and Unitranche

During the credit crunch banks reduced lending to the leveraged market and the number of banks in a leveraged loan syndication fell dramatically. Fund managers and in particular the private equity fund managers saw an opportunity to replace the banks and create a new business line for themselves. The funds began to market debt funds to investors. They were well received: putting money into these funds gave investors like pension funds and insurance companies access to a new asset class – corporate loans, which had previously been the monopoly of the banks.

As well as providing the B-loan financing, like the CLOs these funds created a new instrument – Unitranche debt. In short, the funds would provide all of the leveraged financing- replacing A, B, second lien with a single bilateral or club facility, offered by a handful of funds. This created a new and even bigger pressure of competition to the banks. Many of the former mezzanine fund providers have changed the format of their funds in line with the P/E partnership debt funds.

Debt Restructuring and Distressed Situations

Despite careful planning and structuring, leveraged finance transactions can sometimes result in debt restructuring or distressed situations if the borrower faces financial difficulties or default. Historical default rates for leveraged loans and high-yield bonds have varied over time, with peak default rates reaching 10-12% during economic downturns. In such cases, various stakeholders become involved, each with their own interests and priorities:

- Lenders and Bondholders: These creditors aim to recover as much of their outstanding debt as possible, often through negotiated restructuring agreements or, in extreme cases, bankruptcy proceedings.

- Distressed Debt Investors: Specialized investors may acquire the distressed debt at discounted prices, with the goal of profiting from the eventual restructuring or liquidation of the company.

- Bankruptcy Courts: In cases of formal bankruptcy filings, courts oversee the restructuring process, ensuring adherence to legal procedures and the equitable treatment of stakeholders.

Potential outcomes in debt restructuring and distressed situations include:

- Debt-for-Equity Swaps: Creditors exchange a portion of their debt for equity in the restructured company, effectively becoming partial owners.

- Debt Forgiveness: Creditors agree to forgive or write off a portion of the outstanding debt to improve the company’s financial viability.

- Asset Sales: The company may sell non-core assets or business units to generate cash and reduce its debt burden.

- Operational Restructuring: Significant operational changes, such as cost-cutting measures or business model pivots, are implemented to improve profitability and cash flow.

- Liquidation: In severe cases, the company may be liquidated, with its assets sold off to repay creditors according to the established priority of claims.

Exit Strategies and Refinancing

Leveraged finance transactions often involve significant debt burdens, and companies may seek exit strategies or refinancing options to manage their debt levels over time. Some common approaches include:

- Initial Public Offering (IPO): Private companies may pursue an IPO, allowing them to access public equity markets and use the proceeds to reduce debt levels.

- Recapitalization: The company may issue new debt or equity securities, using the proceeds to refinance existing debt on more favourable terms or extend maturities.

- Asset Sales: Selling non-core assets or business units can generate cash flow to reduce debt burdens.

- Refinancing through New Debt Issuances: As market conditions change or the company’s financial performance improves, it may refinance existing debt by issuing new leveraged loans or high-yield bonds at more attractive interest rates or terms.

- Sponsor Support: In the case of sponsor-backed transactions (e.g., private equity-owned companies), sponsors may provide additional equity capital to reduce debt levels or support refinancing efforts.

- Strategic Mergers or Acquisitions: Companies may pursue strategic combinations or divestitures to optimize their capital structures and reduce debt burdens.

Risks and Rewards of Leveraged Finance

While leveraged finance can provide companies with access to substantial capital for growth and strategic initiatives, it also carries significant risks. High levels of debt can strain a company’s cash flow and increase its vulnerability to economic downturns or industry-specific challenges. Additionally, leveraged finance transactions often involve complex legal and regulatory considerations, requiring careful due diligence and compliance.

However, the potential rewards of leveraged finance can be substantial. Successful leveraged transactions can generate significant returns for investors and enable companies to pursue transformative growth strategies. Moreover, the use of leverage can amplify returns on equity, creating value for shareholders.

Credit Rating Agencies and Risk Assessment

Credit rating agencies play a crucial role in assessing the risk of leveraged finance transactions, particularly those involving high-yield bonds. The three major credit rating agencies – Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch – assign credit ratings to bond issuances based on their evaluation of the issuer’s creditworthiness and ability to meet its debt obligations.

These ratings range from investment grade (AAA to BBB-) to non-investment grade or high-yield (BB+ and below). Credit rating agencies consider various factors when assigning ratings, including the issuer’s financial strength, industry dynamics, competitive position, and management quality. Investors rely on these ratings to gauge the risk associated with investing in leveraged finance instruments and to determine appropriate pricing and yields.

US vs. European Leveraged Finance Markets

While leveraged finance is a global phenomenon, there are some key differences between the US and European markets:

- Market Size: The US leveraged finance market is significantly larger than its European counterpart, with a higher volume of transactions and larger deal sizes.

- Investor Base: The US market has a more diverse and mature investor base, including a larger proportion of institutional investors such as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and mutual funds. In contrast, European leveraged finance relies more heavily on bank lending.

- Regulatory Environment: The regulatory frameworks governing leveraged finance transactions differ between the US and Europe. For example, the US market is subject to the leveraged lending guidelines issued by federal regulators, while European transactions must comply with various national and EU-level regulations.

- Documentation and Terms: Loan and bond documentation, as well as covenant packages, can vary between the US and European markets, reflecting differences in market practices and legal systems.

- Currency: US leveraged finance transactions are typically denominated in US dollars, while European deals may involve a mix of currencies, including euros and pounds sterling.

Despite these differences, the US and European leveraged finance markets are increasingly interconnected, with many global investors and banks participating in both markets.

Examples and Case Studies for Leveraged Finance

To better understand the practical applications of leveraged finance, let’s explore a few real-world examples and case studies:

Example 1: WorldPay

In 2023 Worldpay, the merchant payments business of Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. (FIS), was spun off. A majority 55% stake in the company was sold to the private equity fund, GTCR. GTCR paid $10.175Bn in total and raised nearly 75% through debt: Worldpay raised USD7.375Bn through a USD5.25Bn first lien TLB, a €500m TLB a US$2.175bn secured bond, a £600m secured bond. The debt was rated BA3/BB. Issuing secured loans and bonds allowed GTCR to tap into different pools of investors, increasing demand and competition for the financing. There was lot of demand for the “moderately leveraged loans from CLOs.

The US$ loan priced at SOFR +300bp, while the € tranche priced at Euribor +350bp. The $ bonds priced at 7.5%, the £ at 8.5%.

Interestingly CTGR did not raise any subordinated debt in this transaction.

Example 2: Dell’s Leveraged Buyout

In 2013, Dell Inc., one of the world’s largest computer manufacturers, underwent a leveraged buyout led by its founder, Michael Dell, and private equity firm Silver Lake Partners. The $24.9 billion deal involved a combination of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds totalling $19.6 billion, making it one of the largest leveraged buyouts in history. This transaction allowed Dell to go private and pursue long-term strategies without the pressures of public markets.

Example 3: Valeant Pharmaceuticals’ Acquisition Spree

Valeant Pharmaceuticals, a Canadian pharmaceutical company, embarked on an aggressive acquisition strategy in the 2010s, fuelled by leveraged finance. The company utilized a combination of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds to finance the acquisitions of various pharmaceutical firms, such as Bausch & Lomb and Salix Pharmaceuticals. However, Valeant’s heavy debt load and controversial pricing practices ultimately led to scrutiny and a significant drop in its stock price.

Example 4: Mezzanine Financing in Renewable Energy

Mezzanine finance has played a crucial role in the renewable energy sector, where projects often require significant upfront capital investment. For instance, in 2021, Invenergy, a leading developer of sustainable energy solutions, secured $180 million in mezzanine financing from Blackstone Credit to support the construction of a portfolio of wind and solar projects across the United States.

Example 5: Leveraged Recapitalization at Dunkin’ Brands

In 2020, Dunkin’ Brands, the parent company of Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins, undertook a leveraged recapitalization transaction. The company issued $3.8 billion in leveraged loans and high-yield bonds to fund a special dividend to shareholders and refinance existing debt. This transaction allowed Dunkin’ Brands to optimize its capital structure while returning cash to investors.

These examples illustrate the diverse applications of leveraged finance across various industries and transaction types, highlighting both the potential rewards and risks associated with this financing strategy.